Hello there! This is Fatima, writing to you at the end of Spring 2020. Things have been hectic these past couple of months and we regret not having updated this blog in a while. Since our last post, RISE Team’s band of overachievers (just kidding) have been hard at work publishing some of our first findings on Syrian refugee resettlement. In December 2019, we published our first methods paper--"Listening in Arabic: Feminist Research with Syrian Refugee Mothers”—in Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism. In the article, Neda Maghbouleh, Laila Omar, Melissa A. Milkie, and Ito Peng explore the benefits and challenges of using a feminist approach to research with Syrian refugees in the Greater Toronto Area.

Here’s the backstory: in 2015, the federal Ministry of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship (IRCC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) announced a joint initiative to fund peer-reviewed research on Syrian refugee resettlement through the “Targeted Research: Syrian Refugee Arrival, Resettlement, and Integration” program (483). We proposed a one-year study to investigate forty-one Syrian newcomer mothers’ wellness and mental health. The study consisted of two waves of interviews: one, within the first months of participants’ arrival and the second shortly before “Month Thirteen,” which represented the end of government or public-private sponsorship of the family (483). Although the call for research proposals did not identify gender as a phenomenon of interest, we proposed a project that centered Syrian refugee women’s accounts because the majority of government-sponsored Syrian newcomers were women and children and because, from a feminist epistemological logic, it allowed us to understand processes like globalization and migration from a gender perspective (484). In short, by centering Syrian refugee women’s accounts, we hoped to be better able to understand core migration and resettlement-related issues identified by IRCC-SSHRC like social integration and employment.

Ultimately, a feminist approach shaped the project in three ways. First, to empirically center the accounts of Syrian newcomer mothers, the co-investigators assembled a multi-generational team of researchers that had the necessary cultural and linguistic expertise to productively engage with and interpret interlocuters’ narratives. The inclusion of Arabic-speaking scholars of Syrian and Arab heritage allowed our team to overcome challenges in recruiting participants and eliciting their narratives. By drawing on their own vulnerabilities, identities and experiences our research assistants were able to quickly build rapport with participants, empowering them to share theirs. This was especially the case during the first wave of interviews where women were still processing war- and migration-related trauma and loss (493).

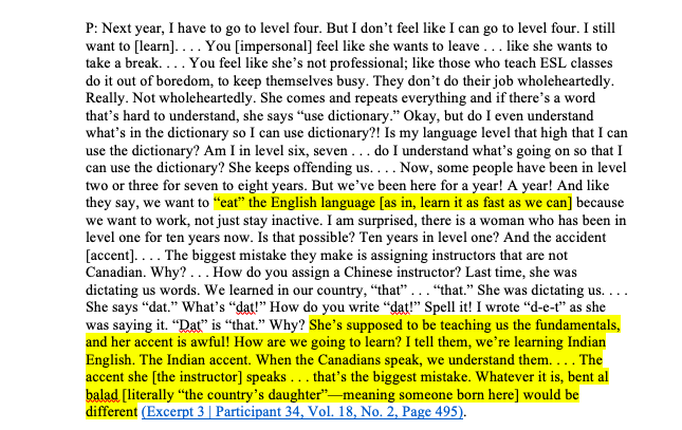

The second way a feminist approach shaped the research involved centering mothers’ language (493). RISE Team’s pilot study was one of the few studies funded by IRCC-SSHRC that engage directly with Arabic-speaking refugees in their native language (486). Interlocuters’ narratives, therefore, had to be translated into English for circulation among ourselves, scholarly and governmental bodies, and for feminist academics and activists who do and do not speak Arabic (486). Our RAs focused on “account” as opposed to “art form” when translating to keep the mothers’ voices “alive”, convey their emotion state by, for example, noting any crying/pauses, and to accurately convey their narratives and meanings (494). However, translating from Arabic to English had its challenges. There is always the risk of losing some idioms, expressions, and ideas in translation (494). Challenges may also arise when translating different dialects, figurative language, and colloquial Arabic expressions. Below, is an excerpt in Arabic and English of a mother’s narrative that illustrates the nuances of translating a passage from Arabic to English when participants code-switch or alternate between languages (496). The hotlink will take you to an audio recording of the excerpt, read by members of our team:

The above excerpt showcases how the meaning of some local expressions (i.e. “nakol [eat] el English”) may be lost in translation, the use of italics to flag how mothers code switch, and how mothers may alternate between languages to ensure certain ideas are communicated accurately. The excerpt also introduces some of the complicated dynamics of eliciting and then transcribing narratives where a participant may express racism against nonwhite Canadians in her criticism of resettlement services (496).

The third way a feminist approach shaped our project was through the involvement of Syrian newcomer mothers in a range of participatory-action activities, driven by their desires, voices, and ongoing consent. Two participants, for example, joined the team as conference panelists at a major Canadian conference. There, they participated in an open Q&A format with the audience where they shared about their involvement in the study, the message they want to convey to Canadians, and why they wanted to participate in the study. We hope that the inclusion of participants in dissemination activities can help destabilize taken-for-granted power dynamics and inequalities in academia (501).

We are grateful for Meridans allowing us to include excerpts of mothers’ narratives in Arabic and for enabling us to record these excerpts. Doing so helped the authors further center Syrian refugee mothers’ accounts and work to destabilize monolingual dominance of English in academic publishing. A huge thank you to IRCC-SSHRC for funding this important research and to our amazing participants for sharing their successes and hardships with us.

The third way a feminist approach shaped our project was through the involvement of Syrian newcomer mothers in a range of participatory-action activities, driven by their desires, voices, and ongoing consent. Two participants, for example, joined the team as conference panelists at a major Canadian conference. There, they participated in an open Q&A format with the audience where they shared about their involvement in the study, the message they want to convey to Canadians, and why they wanted to participate in the study. We hope that the inclusion of participants in dissemination activities can help destabilize taken-for-granted power dynamics and inequalities in academia (501).

We are grateful for Meridans allowing us to include excerpts of mothers’ narratives in Arabic and for enabling us to record these excerpts. Doing so helped the authors further center Syrian refugee mothers’ accounts and work to destabilize monolingual dominance of English in academic publishing. A huge thank you to IRCC-SSHRC for funding this important research and to our amazing participants for sharing their successes and hardships with us.